Pancreatic Cancer Diagnosis: Key Terms Explained

A pancreatic cancer diagnosis can turn your world upside down overnight.

One day you’re juggling work, errands, and everyday life and the next, you’re handed a new vocabulary that sounds like a foreign language. Between scans, lab results, and treatment names that could double as tongue twisters, it’s easy to feel lost before you even begin.

I remember that confusion vividly. That’s why I’ve written this post: to break down some of the most common pancreatic cancer terms into plain, human language, so you can walk into your next appointment feeling a little more prepared and a little less overwhelmed.

When I Was First Diagnosed

The appointments felt like they were moving on a conveyor belt; fast, mechanical, and designed to hit some kind of daily quota. My calendar quickly filled up with scans, blood work, and doctor visits. With every new appointment, I was introduced to new medical terms and tests, all while still trying to wrap my head around the fact that I had cancer, never mind trying to understand the treatment plan.

I know how overwhelming it can feel. My hope is that by breaking down some of these medical terms, it might ease the weight just a little if you’re going through a pancreatic cancer diagnosis.

And just to be clear, I’m simplifying things here. No two tumors or surgeries are exactly alike. Oh, and one more thing: I despise the word journey. It makes it sound like I packed a bag and went on some magical trip. Trust me, this is not that.

Pancreatic Cancer Basics

When you’re first diagnosed, you’ll start hearing a lot of new words. Let’s start with the basics.

Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma (PDAC)

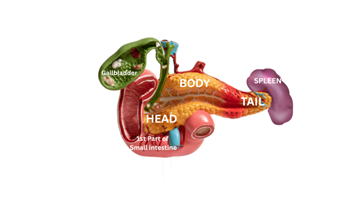

The most common type of pancreatic cancer, PDAC makes up about 90% of all cases. It starts in the ducts of the pancreas, where digestive juices flow, and is often found in the head of the pancreas.

- Represents roughly 9 out of 10 pancreatic cancer cases

- Begins in the pancreatic ducts

- Known for its aggressive nature and challenging early detection

Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumor (PNET)

Much rarer than PDAC, PNETs are a completely different type of pancreatic cancer. They begin in the islet cells of the pancreas, which make hormones like insulin, and can behave in unpredictable ways.

- Far less common than PDAC

- Starts in the hormone-producing islet cells

- Can range from slow-growing to highly aggressive

These two types might sound similar, but they’re not treated the same way. Understanding which one you have helps doctors create a more accurate plan for your care.

Surgery Terms You Might Hear

Once your type of tumor is identified, your medical team may talk about surgery. Here are two terms that come up often.

Whipple Procedure

(Also called a Pancreaticoduodenectomy but no one says that unless they’re trying to win at Scrabble.)

This surgery is usually done when the tumor is located in the head of the pancreas. It’s a complex operation that removes part of the pancreas, part of the small intestine (the duodenum), the gallbladder, and the bile duct. After all that, the surgeon reconnects everything so your digestive system can still work. It’s a big surgery with a big recovery but for some, it offers the best shot at long-term survival.

- Performed for tumors in the head of the pancreas

- Involves removing and reconnecting multiple organs

- Offers the best chance at long-term survival for eligible patients

Distal Pancreatectomy

This surgery removes the body and tail of the pancreas and is often performed when the tumor isn’t located in the head. In many cases, the spleen is also removed because it shares blood vessels with the pancreas.

- Removes the body and tail of the pancreas

- Often includes removal of the spleen

- Typically used for tumors in the pancreas’ tail or body

Chemotherapy

If surgery is possible, chemotherapy often follows. If surgery isn’t an option, chemo may be used to control the cancer. Either way, you’ll probably hear about two common regimens.

FOLFIRINOX

(Pronounced Fall-FEAR-in-nox—and yes, I said “fear.”)

Let’s not sugarcoat it, FOLFIRINOX is strong. It’s often used for people who are healthy enough to handle serious side effects. It’s a mix of four chemo drugs, and let me tell you, it doesn’t come to play. This one can knock the wind out of you, but for some, it also gives the best chance at keeping the cancer in check.

- Combination of four chemotherapy drugs

- Typically used for patients healthy enough for aggressive treatment

- Can cause strong side effects but offers strong results for some

Gemcitabine

(Pronounced Gem-sigh-ta-bean.)

This one is more commonly used and is sometimes combined with another drug like Abraxane. People often call it the “gentler” chemo but “gentle” is relative when you’re in the ring with cancer.

- Common chemotherapy option for pancreatic cancer

- Often paired with Abraxane

- Considered “gentler” but still demanding on the body

Radiation Therapy

Radiation uses high-energy beams (think: super-focused X-rays) to kill cancer cells. It can be used in a few ways:

- Before surgery – to shrink the tumor and make it easier to remove

- After surgery – to clean up any leftover cancer cells

- When surgery isn’t an option – to help control the tumor or relieve symptoms

Radiation is often combined with chemotherapy, a combo called chemoradiation. Because apparently, hitting cancer from one angle wasn’t enough, so they hit it from two.

Tumor Markers

Blood tests can help track what’s happening inside your body. Two you’ll hear about often are CA 19-9 and CEA.

CA 19-9

CA 19-9 is a tumor marker that doctors use to see if cancer might be present or if treatment is working. They track how your levels change over time. But here’s the thing, this test doesn’t work for everyone.

I never had elevated CA 19-9 levels. Normal is 0 to 37 U/mL, and mine stayed low normal, really low normal. The highest I ever saw was 8, even while adenocarcinoma was happily taking over the head of my pancreas. Turns out about 5 to 10% of people don’t produce CA 19-9 because of their genetics, which can lead to false negatives. Gee, lucky me.

- Monitors cancer presence and treatment response

- Not reliable for everyone (5–10% don’t produce CA 19-9)

- Normal range is typically 0–37 U/mL

CEA (Carcinoembryonic Antigen)

CEA is another tumor marker that can be elevated in pancreatic cancer but it’s less specific. Levels can rise for other reasons too, like smoking or inflammation. So while it’s another piece of the puzzle, it’s not a star player.

- Another blood test used alongside CA 19-9

- Can rise due to non-cancer causes

- Useful, but not a definitive indicator

Bottom line: Tumor markers are useful, but not perfect. They’re one tool among many that doctors use to figure out what’s really going on.

Imaging: Scans That Tell the Story

If you’re like me, you probably didn’t know there were different kinds of MRI scans until after you were diagnosed. Here’s what you’ll likely encounter:

Abdominal MRI

An abdominal MRI looks at all the organs in your abdomen; liver, pancreas, kidneys, spleen, intestines, and blood vessels. It gives detailed images of soft tissue to help doctors spot tumors, inflammation, or other issues. The focus is broad, covering a wide area to check for multiple possibilities.

- Provides a full view of abdominal organs

- Helps detect tumors, inflammation, or other abnormalities

- Common first-line imaging tool in diagnosis

MRCP (Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography)

This specialized MRI focuses specifically on your bile ducts, pancreatic ducts, and gallbladder. It uses MRI technology with settings that highlight fluid-filled structures. It’s non-invasive, and in my case, my doctor ordered it with gadolinium contrast. MRCPs are often used to check for blockages, stones, or tumors.

- Targets bile and pancreatic ducts

- Non-invasive and uses special MRI contrast

- Detects blockages, stones, or tumors

ERCP (Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography)

ERCP is different. It’s a procedure, not just a scan. Under anesthesia, a thin tube (endoscope) is passed through your mouth, down your throat, through your stomach, and into your small intestine. The doctor injects dye into the ducts and takes X-rays to look for blockages or narrowing.

- Invasive diagnostic and treatment procedure

- Uses dye and X-rays to visualize ducts

- Can sometimes treat blockages during the same procedure

How Doctors Determine Surgical Eligibility

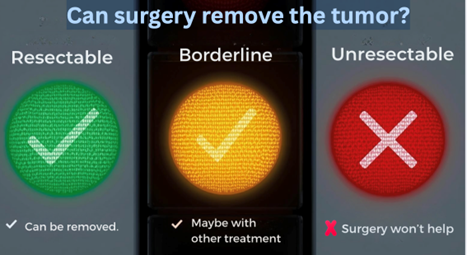

After all the imaging and testing, your surgical team will typically classify your tumor in one of three ways:

- Resectable: The tumor can be safely removed, it hasn’t spread to major blood vessels or organs.

- Borderline Resectable: The tumor is close to critical blood vessels. Doctors may recommend chemotherapy or radiation first to shrink it.

- Unresectable: The tumor can’t be safely removed because it’s grown into major vessels or spread too far. In this case, the focus shifts to treatments that control the cancer and symptoms.

Knowing where your tumor falls helps guide realistic expectations and treatment options.

Facing It, Step by Step

I know this is a lot. You didn’t choose this, and it definitely doesn’t feel like a “journey.” But the more we understand what’s happening, the more we can face it step by step, scan by scan, and term by confusing medical term.

If even one part of this makes your day a little easier, then it was worth writing.

You’re not alone. Reach out.

If this post brought up questions or worries, I’m here to listen. Send what’s on your mind and I’ll help you find clear, compassionate next steps.

Discover more from Dr. Yvette Colón

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.